Black Students at Barnard

Black Students at Barnard

History

Thirty-six years after Barnard College was founded (in 1889), the already acclaimed author Zora Neale Hurston ’28 enrolled as Barnard’s first African American student — her admission was championed by Barnard co-founder Annie Nathan Meyer. By the mid-’50s, African Americans were still not well represented, with only two students per class year.

In the fall of 1968, in the midst of the civil rights, women’s, and anti-war movements, numbers finally reached a critical mass, with approximately 80 Black students living on campus and off. But at the time, Barnard had no Black professors; Black experiences were not integrated into the curriculum; syllabi failed to contain works by African American authors and academics; and at the College’s gates and in its residence halls, Black students and their guests regularly faced harassment from campus security.

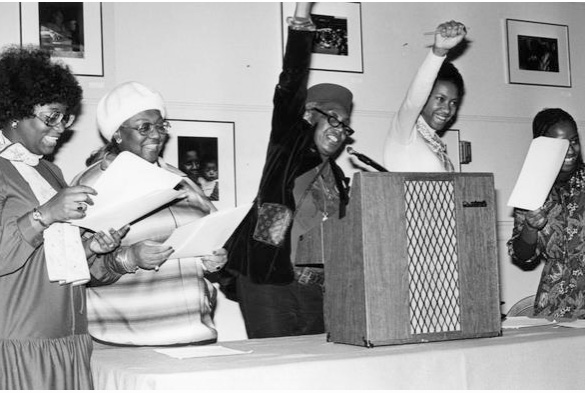

At Columbia, students from both sides of Broadway protested these and other conditions in the spring of 1968 by occupying Hamilton Hall. Then, in the ’68-’69 school year, Black students on campus formed the Barnard Organization of Soul Sisters (BOSS). In February 1969, the group sent a manifesto to Barnard’s president, Martha Peterson. The document argued for an interdepartmental major in Afro-American studies; a voluntary, separate living space for Black students; Black professors; courses that were relevant to African American experiences; improved financial aid; increased recruitment of Black students; soul food in the dining room; and an end to harassment by campus security guards.

Although the demands were supported by nearly all of Barnard’s Black students, the group faced a standoff with the College’s administration, according to the University’s student newspaper, the Columbia Daily Spectator. President Peterson initially said at a faculty meeting that she hoped the faculty and administration would recognize they’d been “remiss” toward Black students and that she considered the demands “reasonable.” Yet in her formal response, issued a week later, Peterson did not grant BOSS the sole power to implement its demands, a central component of the manifesto. The organization rejected her response and held a series of meetings to explain its position. “Our demand for the power to have control over our environment is an extension of the movement of blacks throughout this nation towards self-determination,” the group wrote in the Barnard Bulletin.

As students argued with the administration over their demands, the College created a lounge for them in 121 Reid Hall. In 1969, the Barnard housing office established 7 Brooks, the name given to the seventh floor of Brooks Hall, as a dedicated space where Black women could choose to live. That same year, the school announced the appointment of three Black faculty members — James H. Cone (Religion); Lloyd Delany (Psychology); and Inez Reid (Political Science) — while the Admissions Office began a dedicated effort to recruit Black students. In 1970, Barnard hired Quandra Prettyman (English) as the first Black faculty member to receive a full-time appointment at the College; Prettyman taught at Barnard until her death in 2021.

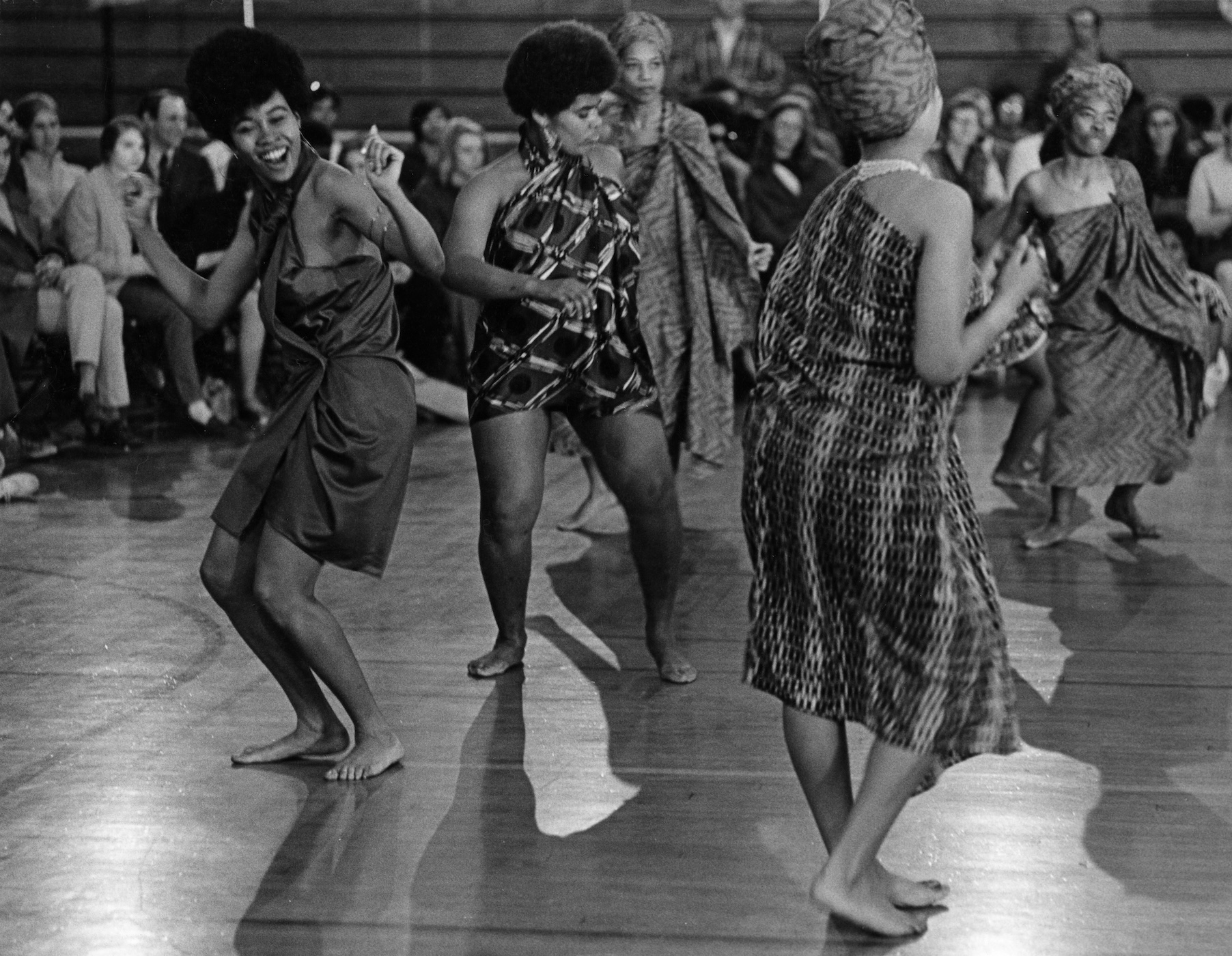

When the inaugural BOSS members graduated in 1972, they left behind a still-honored tradition called the Celebration of Black Womanhood. Originally called the Black Women’s Conference, the event invites Black women from the arts and a range of professions to campus. The first one, in 1972, featured poet Sonia Sanchez and author Toni Cade Bambara and eventually expanded from one day to a full week. Actor and activist Ruby Dee, Planned Parenthood’s former president Faye Wattleton, and lawyer-activist Florynce Kennedy are just some of the speakers who have attended.

In an effort to right a wrong to Dorothy Height ’29 — who had been accepted to attend Barnard in 1929 only to learn shortly before classes began that the quota for Black students had already been met and she couldn’t attend that semester — the College awarded her the Medal of Distinction in 1980, along with an official apology and honorary alumna status. In 2010, to recognize Height’s passing, former Barnard president Debra Spar published an apology letter in The New York Times.

For Women’s History Month 1994, more than a dozen Columbia undergraduates hung a banner from the roof of Butler Hall to recognize the contributions of some of the humanities’ greatest women, including Hurston. When the banner was rolled out again in 2019, Ntozake Shange ’70 was on the list.

As the College moved into the 21st century, Black students continued to push for equity, to build solidarity, and to sustain and represent the legacy of Zora Neale Hurston, as well as that of first-generation college students, international students, and women who are increasing the numbers in STEM fields, business, and more.

Notable Black Alumnae

*Deceased

- Andrea Achi ’07: Curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Alice Baker ’96: Founder of AfroCROWD, a workshop encouraging underrepresented peoples to edit Wikipedia to address biases and gaps in coverage on people of African descent; board member, Wikimedia New York City

- Ayana Byrd ’95: Author, screenwriter, and journalist

- Margaret Cezair-Thompson ’79: Author; senior lecturer in English at Wellesley College

- Edwidge Danticat ’90: Acclaimed author; recipient, MacArthur “Genius Grant” Fellowship

- Thulani Davis ’70: Novelist, librettist, poet, and playwright

- Alexis Pauline Gumbs ’04: Poet, author, and founder of the Mobile Homecoming Trust Living Library and Archive of Generations of Black Queer Brilliance

- * Zora Neale Hurston ’28: Novelist, folklorist, and anthropologist; Barnard’s first African American graduate

- * Jean Blackwell Hutson ’35: Chief curator of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture (1948-1980), librarian, archivist, writer, educator, and advocate for the preservation of Black history

- Gabriella Karefa-Johnson ’19: Fashion editor; first Black woman to style a Vogue cover

- Sharon Johnson ’85: Scholar-practitioner of film, television, and African American arts and literature

- * June Jordan ’57: Poet, essayist, teacher, and activist

- Sydnie L. Mosley ’07: Founder of SLMDances

- Omolola Ijeoma Ogunyemi ’93: Author and poet; PEN/Studzinski Award finalist

- Marilyn Sanders Mobley ’74: Professor emerita of English and African American studies at Case Western Reserve University

- * Ntozake Shange ’70: Poet, novelist, playwright, and feminist

- Asali Solomon ’95: Author; received the National Book Foundation’s “5 Under 35” honor

- Judith Weisenfeld ’86: African American religion scholar; Agate Brown and George L. Collord Professor of Religion at Princeton University

- Charmaine Wilkerson ’82: Journalist, writer, and author

*Deceased

- Adaeze Otue Ezekoye ’66: Community leader, teacher, and human services executive

- * Lila Fenwick ’53: First black woman to graduate from Harvard Law School; former United Nations official; human rights advocate

- * Barbara Ann Rowan ’60: First Black woman prosecutor for the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York

- * Sheila Abdus-Salaam ’74: Associate judge of the New York Court of Appeals

- * Anna Diggs Taylor ’54: First Black woman to be appointed as a federal judge in the U.S. District Court

- * Barbara M. Watson ’39: U.S. diplomat; Ambassador to Malaysia; first Black person and first woman to serve as an Assistant Secretary of State

*Deceased

- Helene Gayle ’76, M.D., M.P.H.: Physician; former CEO of the Chicago Community Trust; 11th president of Spelman College; American Academy of Arts & Sciences member

- Frances Sadler ’72: Barnard Board of Trustees Emerita; associate director of 1199SEIU Training and Employment Funds

- Jean Gaillard Spaulding ’68, M.D.: Psychiatrist, first female African American medical graduate of Duke University; inaugural Chair of the North Carolina African American Heritage Commission

- Deborah Thornhill ’75: Associate Executive Director of Strategic Planning at Harlem Hospital Center

- * Elizabeth Bishop Davis Trussell ’41: Noted psychoanalyst; professor emerita of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University

*Deceased

- Nia Ashley ’16: Writer, filmmaker, and producer

- Akosua Barthwell Evans ’68: CEO, lawyer, and founder of the Black Arts Council (The Friends of Education) at the Museum of Modern Art

- Denise J. Lewis ’66: Business lawyer and urban development expert

- Vernā Myers ’82: VP of Inclusion Strategy at Netflix and founder of the Vernā Myers Company

- Marcia Sells ’81, P’23: Former professional dancer, chief diversity officer at the Metropolitan Opera, dean of students at Harvard Law School

- Nina Shaw ’76: Entertainment industry attorney and co-founder of Time’s Up

- * Norma Merrick Sklarek ’50: First licensed African American woman architect in New York State

- Ebonie Smith ’07: Grammy Award-winning music producer

*Deceased

- Erinn Smart ’01: Silver medalist in fencing at the 2004 Olympics